Mortgage History 101

Like ’em or hate ’em – ever wonder where the modern mortgage came from?

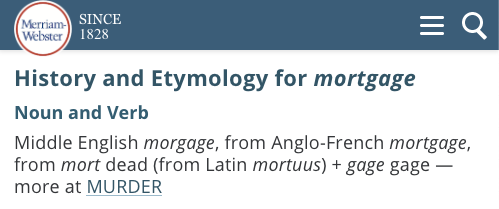

Where does the word “mortgage” come from?

The mortgage. You don’t have to look far beyond your own opinion of them to get a feel of how people think about it. What happens when you look up the definition of mortgage?

Hmm – mortgage and murder in the same sentence, eh? That’s nice.

And, because we should always fact-check, especially with information on the internet, there’s a little bit more about it on the Economist – which I suppose is one of the better sources out there.

When did the mortgage start?

There seem to be recorded instances of mortgages as far back as Mesopotamia.

I’m no historian, but I know enough about how dodgy the facts are when it comes to ancient history that it’s probably safer to start our story a little closer to where we are.

Since we trace our origins back to Europe anyway, let’s take our time machine back to the feudal times in England.

Imagine if you required permission from your landlord to leave your property. To that you’d probably exclaim, “That’s absurd!” What if I told you that at some point in time, the landlord could dictate whether or not you could change your occupation or even get married. Gives new meaning to the lord in landlord, doesn’t it? This was a reality for people under the system of serfdom.

A scene depicting two serfs and four oxen pulling a plow. From the Luttrell Psalter.

As a tenant under that system, to live on the land meant that you were required to perform a service in return for the one who owned the land. Now, one could argue that despite our freedoms now, we’re bound by similar circumstance in that we’re tied to our jobs in order to keep our homes. Since we have choice over our own professions and aren’t bound by indentured servitude, I like to think we’re a little bit better off now – judging by the expression of our serf friend here.

I feel you, my friend. I feel you.

It got better though, didn’t it?

Yes… but it had to get worse first. Introducing: the Black Death.

Admittedly, the main character in Monty Python and the Holy Grail is the legendary King Arthur, who supposedly lived between the 5th and 6th century – the Black Death happened in the 14th century but my point is this:

A lot of people died. A lot.

Hang in there, buddy! It will get better… eventually.

Interestingly, the sudden decline in population and increasing shortage of labour was favourable to the serfs – they suddenly had more bargaining power. There likely was no single event that abolished serfdom but a series of revolts like the Wat Tyler Rebellion certainly helped in replacing serfdom with free peasantry. These peasants, also known as free tenants, weren’t necessarily better off economically than prior to the abolition of serfdom but they did have more rights.

There’s more! But first, a coffee break.

That was a lot to digest. Make yourself a cup of tea as we continue to relive the reality of English peasants. What better way to immerse our selves than to once again visit the famed historians that is Monty Python:

Now that we have revisited the violence inherent in the system, we have to pause for a second and talk briefly about mortgage law. Because I’m not a lawyer, I had to go to Wikipedia to make sense of all the jargon. Flying in the face of academia and with a big thanks to Jimmy Wales, I finally get to accomplish my childhood dream – use Wikipedia as a reference source.

Before mortgage, there was vif-gage and wadset.

Linguistics factoid: Without getting too deep into the rabbit hole, you might be wondering why England was using French and, what looks like, gibberish. England was conquered by the Duke of Normandy in the 11th-century – from the kingdom of France. The reason it’s unfamiliar is because back then, they spoke Middle English, which lasted until the 15th-century. The English language as we know it now has changed a lot since then.

Do you watch Vikings? Clive Stranden plays Rollo, the first Duke of Normandy – his descendant, William the Conqueror was the Duke of Normandy in the 11th-century. In fact, most European monarchs to this day can be traced back to him!

The wadset came first.

There was a time when interest loans were illegal (I know, right?!), and so they used what’s called a wadset. A borrower who needed some cash would go to a lender and, using whatever property they had, would get a loan based on their consideration (their home, or their collateral).

Sound familiar? This is where the similarity ends though!

It was an extremely broken system; unfortunately, the way the contract worked was that the wadsetter (lender) became the absolute owner of the property and thus had the right to do with the property whatever they want – including refusing to give it back to the wadsettee (borrower).

In other words, whether the lender would make good – on what was essentially a pinky-promise – came down to what kind of person they were. Good luck if you needed a loan in medieval England and you found a bad lender!

They eventually figured out a way to have a separate contract binding the lender to their promise that was executed at the same time as the wadset, but it really makes you appreciate our current system, doesn’t it?

Then came the vif-gage.

“Vif” means live and “gage” means pledge – a live pledge. It was repayment of a debt (e.g. a gage of land, or what we now know as real estate debt) using the profits or crops produced on the land. This is different from a dead pledge in that the debt is self-redeeming, i.e. what is produced pays back the debt directly.

That doesn’t sound that bad…was it?

Well, it certainly sounds progressive at first, doesn’t it? One minor hiccup though…

The live gagee could use novel disseisin to just claim their property back. How? Apparently, this was a legal loophole devised by Henry II to take land from King Stephen (prior to succeeding him as king) and a person could just take a land dispute to the royal courts and the property would immediately be returned to the claimee. According to Wikipedia, “the question of true ownership was dealt with later.”

Basically, in a case of second-grade na-na-boo-boo, it’s like promising your friend on the playground that whoever wins the game of tag will get your recess snack; then, when you lose, you tell the teacher your friend was trying to take your snack and munch on it while you sit there listening to her lecture the both of you. This put way too much power into the borrower’s hands.

Now you can see why the live gage (mortgage) fell out of favour for the dead gage.

These two types of gages, or pledges as we’ve learned, actually existed concurrently! The dead gage, also known as dead wad in Scottish dialect (remember the wadset?), was an arrangement “whereby the rents and profits were taken in lieu of interest but did not reduce the debt.”

Of course, it continued to evolve until it eventually became what we know today, where we have mortgage payments that reduce interest and principal simultaneously.

You can understand why I needed Wikipedia now, eh?

Like I said, as with most things in history, there is a lot of incomplete and potentially inaccurate information out there. As a hobbyist historian, though, I hope I’ve done it justice in a way that was fun – or at least made sense!

I’m impressed you got this far. What’s your prize, you say?

Click here to win more information about the writer (me)

OR